-

- News

- Books

Featured Books

- pcb007 Magazine

Latest Issues

Current Issue

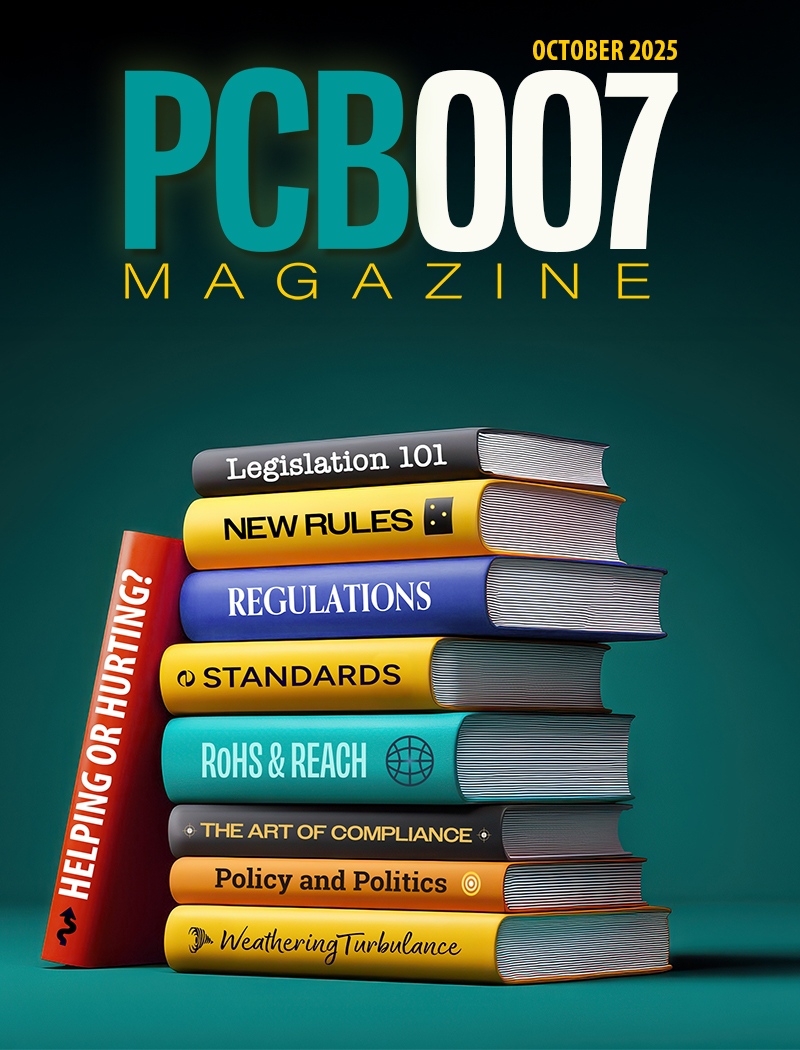

The Legislative Outlook: Helping or Hurting?

This month, we examine the rules and laws shaping the current global business landscape and how these factors may open some doors but may also complicate business operations, making profitability more challenging.

Advancing the Advanced Materials Discussion

Moore’s Law is no more, and the advanced material solutions to grapple with this reality are surprising, stunning, and perhaps a bit daunting. Buckle up for a dive into advanced materials and a glimpse into the next chapters of electronics manufacturing.

Inventing the Future With SEL

Two years after launching its state-of-the-art PCB facility, SEL shares lessons in vision, execution, and innovation, plus insights from industry icons and technology leaders shaping the future of PCB fabrication.

- Articles

- Columns

- Links

- Media kit

||| MENU - pcb007 Magazine

Estimated reading time: 18 minutes

Contact Columnist Form

Happy’s Essential Skills: Technology Awareness and Change

From Happy Holden: A long-time printed circuit-industry friend of mine, Martin Tarr, an instructor at University of Bolton, UK, is a leading expert on change. He wrote an excellent tutorial for his university course on electronics manufacturing. With permission from Tarr, I am including a portion of it here as the basis of this column, starting after the graph in Figure 2. But first, a few thoughts of my own.

Introduction

Being part of the electronics industry is like holding a tiger by the tail. Electronics has changed our life more than any other industry, and will continue to do so. Only the pace of change is accelerating! This is all due to that little piece of ‘glass’ known as the integrated circuit. When I was in college, the IC was just starting out, so my first stereo amplifier was tube based. I still use my AKAI 7-inch reel-to-reel tape deck and it is all tubes. In electrical engineering labs, I used ICs that had only 12 transistors in them. Today, modern microprocessors from Intel or AMD have over 1,000 million transistors and the number is still growing. The future will see electronics consuming more and more industries.

As accustomed as we are to the changes electronics has created, we may be the casualties of paradigm paralysis[3], as the 21st century may belong to genetic engineering. Already they are creating bacteria by genetic manipulation that will ‘live’ in sealed ICs and perform tasks never possible with silicon electronics. The point of all of this is that change is the one factor we can be sure of.

In my observations, technology changes come in waves. The early innovators or initiators help pioneer something new. As seen in Figure 1, they are a meager 3–5% of the industry. The close followers see that disaster has not set in and they “assumulate” the technical change also. They can be from 5–15% of the industry. But then, the more timid and risk adverse begin to see that this change seems to be working out, which expands the BIG WAVE as everyone jumps on board. This lasts for quite a while, when finally, the last few hold-outs finally agree that the new-fangled stuff seems to be OK. The final integration wave can take from 5–15 years.

What I call my ‘wave theory’ also has been observed as the “S-Shaped Curve of Technology Adoption,” as shown in Figure 2. I think we are talking about the same phenomena, because if you integrate the area under my ‘three waves’ it will look like the ‘S-Shaped curve.’

This ‘sigmoid’ curve is an integration of the normal bell-shaped distribution curve and is highly used in predicting business cycles, population trends, e-learning and many other phenomena. The adopters of innovations break down into seven categories:

- Innovators: 1%–2.5% (the Pioneers)

- Early Adopters: 10%–13.5% (the Optimists)

- Early Majority Followers: 30%–34% (the Pragmatists)

- Late Majority Followers: 30%–34% (the Aspirers)

- Laggards: 12%–16% (the Very Late Followers)

- Skeptics: 1%–3% (the Got-to-do-it Group)

- Rejecters: < 1% (the May-Never-do-it Group)

Figure 1: Waves of technology adoption.

Figure 2: The S-shaped curve of technology adoption.

Why Change?

by Martin Tarr

Changes of all kinds are inevitable in business, whether they involve adopting new technology or reorganizing to meet a challenge. But they don’t just happen to us, they must be managed. Having said that, change is not always welcomed, and whether you make positive or negative responses to the challenge of change will depend on your situation, your personality, and your previous experience of change. Those with more positive responses regard change as an opening or opportunity, whereas those with more negative responses see change as a threat to a familiar or established situation.

Note that we are much more likely to think negatively about changes that are imposed than about changes over which we have control, and people’s perceptions of situations are important in deciding whether they will see problem or opportunity.

Pressures for Change

Changes for organizations may come from pressures within the organization or from forces outside it. The latter are normally outside the control of the management and include factors such as movements in interest or exchange rates or the rate of inflation, and alterations in demand for products and services. The changes may be caused by competitors, or by modifications to the legal or political framework in which the organization operates. The types of change will depend on the nature of the organization but, whatever they are, management action is necessary to adapt to the new situation.

When influences are outside its control, an organization can only respond. However, any internal changes, such as the appointment of new people, the provision of facilities and experimentation with new methods, can involve planning, decision-making and implementation processes.

Types of Problems

Planning to introduce change into an organization implies a situation where we find ourselves part of the change and need to decide how to go about making the move. Depending on the context, exactly what the change needs to be may be more or less clear; consequently, how to implement the change may be more or less certain. So change is a kind of problem.

Problems are often divided into two types:

- quantifiable or ‘hard’ problems which have single solutions

- more intractable or ‘soft’ problems which have no single solution

Relating to change, a hard problem might be selecting the best way of getting from the present state to an agreed future state, whereas a soft problem is presented by a change where the intended destination has still to be discovered. In practice, there is not always a clear distinction between hard and soft, but the more intractable change problems are always at the ‘soft’ end of the spectrum (Table 1).

Table 1: Hard and soft problems have distinct characteristics:

An alternative description of change is as a messy problem, and another helpful concept is that of the problem being either ‘bounded’ or not. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show typical characteristics of a bounded, well-defined problem and of an unbounded mess.

Figure 3: Characteristics of a bounded problem[1].

Figure 4: Characteristics of an unbounded problem or ‘mess’[1].

Many ‘bounded’ problems represent what may be thought of as difficulties, that require effort (money, extra administration, or whatever) rather than the problem-solving flair that is demanded by messes.

Whether you frequently have messes to deal with will depend to some extent on the kind of organization. There appears to be a relationship between the degree of involvement in decision making and commitment to the goals of the organization; whilst rapid decisions often come from a more hierarchal structure, this is not necessarily a good thing!

Differing Perceptions of Problems

All problems can be approached with common sense, but your version of common sense will be colored by the culture in which you operate, your previous work experience, your educational background and your experience of family life.

Common sense cannot be relied upon to supply a foolproof method for solving complex problems or conceiving and implementing changes that are of the unbounded, unstructured messy type. For an example of how beliefs and culture have a fundamental impact on the way problems are perceived, think back to the Teamster’s strike 50 years ago and the fundamental differences between Jimmy Hoffa and Robert Kennedy, who were reported as being ‘emotionally incapable of reaching an agreement.’

Whilst this example is somewhat extreme, even under normal circumstances there will be differences in perspectives as to what the problems are and how they should be dealt with. The implication is that, if you want to influence someone or change their mind, there is no point in bombarding them with facts or obvious solutions that they are going to filter out or dismiss because of their cultural background. The way to try and make them change their mind is first to understand why they are thinking the way that they do.

It is important to listen to what they say, and think not only about the truth of the argument being presented, but how they came to believe it in the first place. Once you have got that far, you should be able to establish some common ground from which you can start to talk. It is useless for you to start pointing out the error of their ways, and offer your own version of the facts or solution. You will end up in meaningless, divisive argument.

Representing Complexity

Change situations are frequently very complex, and characterized by many interacting forces, both inside and outside the organization. Because verbal descriptions have great difficulty in handling such complexity, drawing a diagram can aid understanding. Similarly, proposals for change can be complex, and using diagrams can help communicate both with those who need to approve the proposals and with those who may be affected by them.

The diagrams don’t have to be complex and most will be made of selected words, pictures and symbols. Typical diagrams might be:

- Mind maps

- Input/output diagrams

- Flow block diagrams

- Flow process diagrams

- Activity sequence diagrams

These last three present similar information but at increasing levels of generality, focusing respectively on specific equipment, process descriptions, and equipment independent activities.

- Control loop diagrams

- Relationship diagrams

- Systems maps

- Influence diagrams

Influence diagrams are a hybrid of relationship diagrams and systems maps but go further in seeking to define the influences which components have on each other.

- Multiple cause diagrams

Working in Groups

Managing change is about managing messes, but also about managing people, specifically groups of people. When an individual joins the group, they are making a trade-off between self-autonomy and the benefits of group membership. We speak about three types of ‘contract’ that are entered:

1. A ‘formal contract’ covers things like group objectives, terms of reference, leadership and responsibilities, in exchange for which payment is made.

2. The ‘informal contract’ is about agreed procedures within the group that are tacitly understood, such as the way decisions are made and how disagreements are handled.

3. The ‘psychological contract’ is concerned with all the psychological aspects of the group and of the individual, and covers such things as the degree to which the group will tolerate and handle interpersonal issues, and how much support the individual expects within the group.

Within groups, individuals will interact, and the larger the group the larger the number of possible interactions. Each interaction is an opportunity for conflict or misunderstanding, so large groups will almost inevitably fail to operate efficiently. As the group size increases, communication is reduced, members feel less involved in the process, alienation increases and commitment to the project decreases. Group effectiveness is reported as being highest at around six to eight people.

Groups of course don’t start out fully formed and fully functional. Tuckman analyzed the stages of group development and summarized them in a four-stage scheme:

- Forming—formal contracts such as purpose are established, but everyone tries to establish his identity with the group.

- Storming—a state of conflict where all formal points established are challenged and re negotiated, to create a realistic formal contract. At the same time, hostility and personal agendas lead to the emergence of informal contracts.

- Norming—here the group moves on to fix how well it should work, and how decisions should be takes, and sets ideas of commitment and the degree of openness and trust.

- Performing—the state characterized by peak activity!

Systems Intervention Strategy (SIS)

Systems ideas are important to the study of change, and can be used to structure the process of understanding, planning and managing change. You will probably be familiar with general system concepts, but this is a reminder of how a system is defined:

- A system is an assembly of components connected in an organized way.

- Components are affected by being in the system, and the behavior of the system is changed if they leave it.

- This organized system of components does something.

- This assembly has been defined as being of interest.

The components of which a system is made may also be referred to as elements and sub-systems, the latter term recognizing that certain components may be complex assemblies and that they have a function that is defined by the overall system of which they form a part.

SIS is one of a family of systems approaches. Although many of these systems approaches are hard methods, because they focus on things, SIS also has an appreciation of the importance of process, which is a feature of most soft methods.

SIS spans a considerable space between hard and soft extremes (Figure 5). An alternative method for management change, Organizational Development (OD) operates nearer the soft approaches part of the spectrum.

Which of the two approaches will be appropriate will depend on the person implementing the change and the characteristics of the change involved.

Figure 5: The scope of Systems Intervention Strategy[1].

SIS has three overlapping phases (Figure 6):

- Diagnosis—the process by which you develop an angle from which to tackle a set of change problems, and in which the purposes of change are clearly identified

- Design—the phase in which alternative options of achieving change are suggested and explored

- Implementation—starts with a commitment to see change carried through, but then develops a means for bringing the desired change about and sees it through

Figure 6: The three overlapping phases of SIS[1].

The initial stages in SIS are to:

- Define the boundaries (rationalize) and perspective

- Identify problem owners at each stage

- Describe the system:

- input/output diagrams

- systems map

- influence diagrams

Use different views to develop an angle

Figure 7: A general model of Systems Intervention Strategy[1].

The phases in Figure 6 are deliberately overlapping, because, for example, questions of implementation beneficially influence design. Whilst this is the simplest way of looking at SIS, in practice most change is cyclical or iterative, and a better general model of Systems Intervention Strategy is shown in Figure 7.

Note the central cloud in Figure 7 that is labelled ‘problem owner’. The dotted lines indicate that the ideas process is paramount; in operating this methodology, you need regular discussions with the problem owners to test out your ideas and check your thinking against an external reference.

In the process of using systems ideas to plan and manage change, there is a tension between the need to explore the wider aspects of the problems and the need ultimately to implement a single set of changes, as shown schematically in Figure 8. At the start of the process your knowledge of what is required will be low, and the possible options for what might be done correspondingly large. However, ultimately, when one option is finally put in place, you are implying that all that is required to be known is known, and the opportunities to change have been reduced from many to one.

Figure 8: The overall challenge of change: to reduce the number of things that could be done to one set of things that should be done[1].

Such smooth curves are deceptive. In reality, the processes of system description, developing and selecting options proceed in an erratic and spasmodic manner. A better image of our process of intervention is one of cycles of convergent and divergent thought (Figure 9), alternately converging on one part of the problem, and then opening new domains in which options may exist.

Figure 9: SIS as cycles of divergent and convergent thinking.[1]

What Is Organizational Development?

Derek Pugh, one of the Organization Development (OD) gurus, describes four principles for understanding change:

- Organizations are organisms

- Organizations are occupational and political systems as well as rational resource allocation systems

- All members of an organization operate simultaneously in all three systems

- Change is most likely to be acceptable where people are basically successful but have tension and failure in some part

Pugh recommends anticipating the need, diagnosing the nature of the required change, and managing the change process. His “six rules for managing change” are:

- Work hard at establishing the need for change

- Think through the change

- Initiate thorough informal discussion to get feedback and participation

- Encourage objections

- Be prepared to change yourself

- Monitor the change and reinforce it.

Organizational Development (OD) uses a range of change approaches and techniques that have four distinguishing characteristics:

- A planned strategy rather than ad hoc changes is demanded.

- A range of disciplines (including behavioral science, organization theory, psychology, sociology, anthropology and political science) is used to develop skills to manage change.

- The fit between the change process and the challenge makes the difference between success and failure.

- An external facilitator is normally needed to help in planning and managing change processes.

Such a facilitator, the OD consultant, must be from outside, be knowledgeable and skilled over change procedures, possess the personal characteristics to be accepted, and have the social skills to establish rapport and creditability.

Typically, an OD approach is appropriate where:

- An organization is failing to accomplish its objectives, and the nature of the current organization is contributing to this failure

- An organization wishes to improve its existing capacity to adapt more readily to environmental changes

- An organization intends to adopt new technologies or new ways of working that require changes in structure, systems and attitudes

- The creation of new operating units gives the opportunity to design new management structures and operating systems from scratch

Figure 10 provides a generalized description of the stages of the OD process. It is of course a recurring cycle because change is continuous, and review of the organization’s capacity to respond to changes effectively must also be continuous.

Figure 10: The Organizational Development process[1].

OD is not one method, but a range of strategies. Those that are most frequently used are listed (italicized) in the boxes of the matrix of Table 2. This OD matrix, devised by Pugh, is a conceptual framework for understanding and diagnosing what change is necessary in an organization, what methods to consider, and which directions to go in initiating the change process.

Note that the rows of the matrix represent the different levels of analytical focus within the organization, whereas the degree of intervention is represented by the columns of the matrix. The left-hand column is concerned with current behavior symptoms that can be tackled directly, whereas moving to the second and third columns requires a greater and greater degree of intervention and commitment by the organization.

There are three rules of thumb basic to successful OD:

- Get participation

- Get resources (time to think; OD advice and help; backing of senior and top management)

- Start small, but start real (nothing succeeds like success, but nothing fails like failure)

Implementing Change

Whether OD or SIS models are used, implementation is vital for change management. The degree of participation that is possible will of course depend on the constraints surrounding the change as well as its drivers, but typically change implementation requires careful and sensitive, but positive and effective management, where a participative approach is maintained, even though a more directive style of leadership may be recommended to deliver the change on time.

The strategy for implementing change is important – based on a survey of 93 companies in the USA, Alexander created a list of ten problems in implementation:

- Implementation took more time than was originally allocated.

- Major problems surfaced during implementation that had not been identified beforehand.

- The co-ordination of the various implementation activities was not creative or imaginative enough.

- Competing activities and crises distracted attention from implementing the decision.

- Employees did not have the necessary skills.

- The training and instruction given to the lower-level employees was inadequate.

- Uncontrollable factors in the environment had an adverse impact on implementation.

- The leadership and direction provided by departmental managers was of poor quality.

- Certain key implementation tasks and activities were not defined in enough detail.

- The information systems used to monitor implementation were inadequate.

Alexander also identified some key features of successful change:

- Two-way communication with all employees.

- Start with a good concept or idea.

- Obtain employee commitment and involvement – ideally involve everyone in the formulation of change strategy from the beginning.

- Provide sufficient resources – money, human resources, technical skills, time and attention from top management.

- An implementation plan or strategy, so that problems are addressed.

Clearly implementation planning will draw on your experience of project planning with appropriate use of bar charts and critical path analysis.

Other Insights into Change

Huse

Huse suggested a number of factors for decreasing resistance to change:

- Take account of needs, attitudes, beliefs

- Demonstrate personal benefit

- Use supervisor/change agent with the adequate prestige, power and influence

- Provide specific information about group/behavior

- Create shared perception of the need for change

- Use change agent with sense of belonging to the changed group

- Use group cohesiveness

- Involve the supervisor in the job situation (not off the job)

- Open communication channels

Kotter and Schlesinger

Kotter and Schlesinger, in diagnosing resistance to change, exposed four common reasons:

- Parochial self-interest (desire not to lose something of value)

- Misunderstanding of the change and lack of trust

- Different assessments (belief that the change doesn’t make sense for the organization)

- Low tolerance for change

For dealing with resistance they recommend:

- Education and communication

- Participation and involvement

- Facilitation and support

- Negotiation and agreement

- Manipulation and confrontation

- Explicit and implicit coercion

The choice will depend on situational factors such as the speed of the change, the amount and type of resistance, the position of the initiators (in terms of power, trust, etc.), the locus of data and implementation energy, and the stakes involved.

Table 2: The Pugh OD Matrix Diagnosis and methods of initiation of change[2].

References

1.Tarr, Martin, Change Management, from AC062 MS Electronics Manufacturing degree program course materials at University of Bolton, UK, used with permission.

2. Pugh, Derek, “Understanding and Managing Change Through Organizational Development,” Change Management, vol. 2, pp. 61–68, The London Business School Journal, 2009.

3. Paradigm Paralysis, John C. Harrison, 1994.

Happy Holden has worked in printed circuit technology since 1970 with Hewlett-Packard, NanYa/Westwood, Merix, Foxconn and Gentex. He is the co-editor, with Clyde Coombs, of the recently published Printed Circuit Handbook, 7th Ed. To contact Holden, click here.

More Columns from Happy’s Tech Talk

Happy’s Tech Talk #43: Engineering Statistics Training With Free SoftwareHappy’s Tech Talk #42: Applying Density Equations to UHDI Design

Happy’s Tech Talk #41: Sustainability and Circularity for Electronics Manufacturing

Happy’s Tech Talk #40: Factors in PTH Reliability—Hole Voids

Happy’s Tech Talk #39: PCBs Replace Motor Windings

Happy’s Tech Talk #38: Novel Metallization for UHDI

Happy’s Tech Talk #37: New Ultra HDI Materials

Happy’s Tech Talk #36: The LEGO Principle of Optical Assembly