-

- News

- Books

Featured Books

- pcb007 Magazine

Latest Issues

Current Issue

Advancing the Advanced Materials Discussion

Moore’s Law is no more, and the advanced material solutions to grapple with this reality are surprising, stunning, and perhaps a bit daunting. Buckle up for a dive into advanced materials and a glimpse into the next chapters of electronics manufacturing.

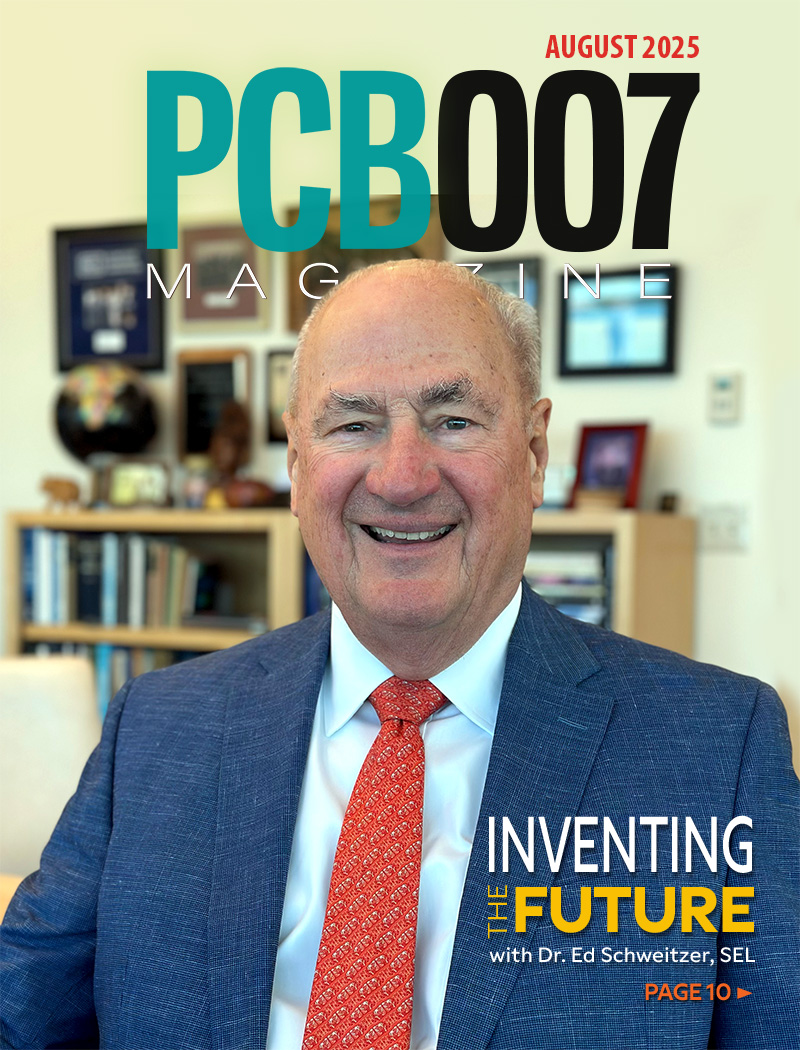

Inventing the Future With SEL

Two years after launching its state-of-the-art PCB facility, SEL shares lessons in vision, execution, and innovation, plus insights from industry icons and technology leaders shaping the future of PCB fabrication.

Sales: From Pitch to PO

From the first cold call to finally receiving that first purchase order, the July PCB007 Magazine breaks down some critical parts of the sales stack. To up your sales game, read on!

- Articles

- Columns

- Links

- Media kit

||| MENU - pcb007 Magazine

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Elementary, Mr. Watson: IPC Standards, A Love Story

In the fall of 1998, I was a novice in the printed circuit board design field, beginning a two-semester course at a community college in San Marcos, California. (Fun fact: I found myself teaching this same course decades later.) Although I was shifting my career from an electronic technician to a PCB designer, I sat nervously as the class started, and the instructor began handing out several paperback-bound books that looked more like a pamphlet on steroids.

As he announced that these would be our textbooks for the course, I began reading the titles: IPC-2221, Generic Standard on Printed Board Design; IPC-2222, Sectional Design Standard for Rigid Organic Printed Boards; and IPC-T-50, Terms and Definition for Interconnecting and Packing Electronics. Those “textbooks” were my introduction to IPC standards. Unbeknownst to me, those basic standards became my reference for every design I would do moving forward. Since those early days, my love and respect for the standards and IPC have only deepened.

I quickly learned several major lessons about this great organization. First, IPC has aimed to standardize electronic equipment, assemblies, and production requirements. IPC’s objective was to focus more on manufacturing than the PCB design itself. The few standards that covered the PCB design process ensured the highest PCB quality per manufacturing and assembly. In recent years, they have expanded into more specific topics, such as high speed/frequency and other fantastic topics and guidelines. That original objective remains: standards imply a level of quality or attainment. That focus is understandable when you see where and, more importantly, when they were founded.

The Start of Standards

With the close of World War II, the first PCB designs were used in military systems, such as the MK53 Proximity Fuse, which automatically detonates an explosive device when it approaches a certain distance from its target. After the war, many of these military patents were released to the public sector, which caused a flood of new products in the early 1950s (affectionately known as the digital age), all backed by the invention of the first transistor at Bell Laboratories on Dec. 23, 1947. They say necessity is the mother of invention; the result was the organization of IPC in 1957.

For me, I developed a love and passion for the PCB industry, however, I quickly learned that not everyone has shared my enthusiasm regarding IPC standards. Even today, when I ask some major companies if they use them, they often say they don’t. That’s interesting to me. They’ll tell me, "We don't believe in them,” “We don't need them," or "We do our own thing." I would even go so far as to say that this viewpoint is prevalent throughout our industry.

I'm curious: What if we applied that same attitude to other areas? To illustrate my point, let's say you are responsible for building a house and you decided not to use a tape rule, a level, or a plumbline. Would you say, “I don’t believe in those things.” Would you be able to trust that an inch really means an inch? What about those pesky city regulations and building inspections? Those are definitely out and not needed, right? Everyone knows they’re only there as a way for the city to collect fees. I think you can see that the result of such an endeavor would be disastrous. The same can be said for our PCB designs.

Why You Should Use IPC Standards

In PCB design, and especially manufacturing (which IPC standards focus on), is a quality, repeatable manufacturing process; following the standards is essential. For example, understanding the difference between Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 directly impacts how you design your PCB based on specifications, performance, and reliability. Just because you may not follow IPC standards, I can almost guarantee that your fabricator and assemblers do.

I recently spoke to one of the top fab/assembly houses in the nation, and the person I was talking to made the point that when a fab or assembly drawing is issued, it’s a binding contract between that company and the fab or assembly house in the production of the board. Even though you may not call out specific IPC standards, this facility still follows them in their processes. It is just a good practice in their words, because it is the "standard."

So, suppose the fab/assembly house follows IPC guidelines. In that case, it might just be a good practice that I first understand each guideline and ensure everyone follows them. It’s essential to understand what the fab/assembly house is doing and expects from your design. There’s also the concept of interoperability: Adhering to IPC standards ensures that different vendors and facilities worldwide can easily manufacture and assemble your PCB designs. That promotes interoperability and reduces the likelihood of compatibility issues. This means that just because you can place symbols on the schematic and the footprint on the PCB doesn't mean that the fab and especially the assembly house can build it without significant risk.

It all begins with the PCB designer. I still have those original three IPC standards on my desk when designing a PCB, and following them helps me develop design consistency and provide a consistent framework for designing PCBs. I can maintain design consistency across different projects and teams within an organization. Design consistency in PCB design refers to the practice of maintaining uniformity and coherence across various aspects of a PCB layout. This ensures that different sections of the board work together seamlessly, and that the design is easily understood and replicable.

Having said all this, the primary reason to use IPC standards is risk mitigation: By following established industry standards, designers can mitigate the risks associated with design errors, manufacturing defects, and reliability issues. That can lead to more successful product launches and fewer post-production issues. On the flip side, a design that didn't follow the standard manufacturing criteria brings a significant risk for the assembler, which means they may most likely have a higher failure rate. They will need to rebuild or rework many PCBs to get your number of good boards, which leads to wasted material, time, etc. The thing is, that wasted material and time is not really “lost,” but is just passed back to you as an increased quote price to do the job. Compliance with IPC standards leads to more efficient and streamlined production processes. Reduced rework, scrap, and improved yields can result in cost savings. Remember, cost savings means increased profit.

Conclusion

IPC standards are continuously updated to incorporate the latest technological advancements and best practices. These standards don't get changed in a vacuum, but rather, committees of people like us walk through them and keep them current. I enjoyed sitting on the IPC-2221 steering committee at IPC APEX EXPO 2023 in San Diego. I am excited to help develop these standards, maybe for the next nervous student sitting in a classroom wanting to learn PCB design. I hope they fall in love with both the standards and the organization of IPC. I encourage you to get involved.

John Watson is a professor at Palomar College in San Marcos, California.

More Columns from Elementary, Mr. Watson

Elementary Mr. Watson: Running the Signal GauntletElementary Mr. Watson: Routing Hunger Games—May the Traces Be Ever in Your Favor

Elementary, Mr. Watson: Why Your PCB Looks Like a Studio Apartment

Elementary Mr. Watson: Closing the Gap Between Design and Manufacturing

Elementary, Mr. Watson: Rein in Your Design Constraints

Elementary Mr. Watson: Retro Routers vs. Modern Boards—The Silent Struggle on Your Screen

Elementary, Mr. Watson: PCB Routing: The Art—and Science—of Connection

Elementary, Mr. Watson: Design Data Packages—Circle of Concern or Circle of Influence?