-

-

News

News Highlights

- Books

Featured Books

- pcb007 Magazine

Latest Issues

Current Issue

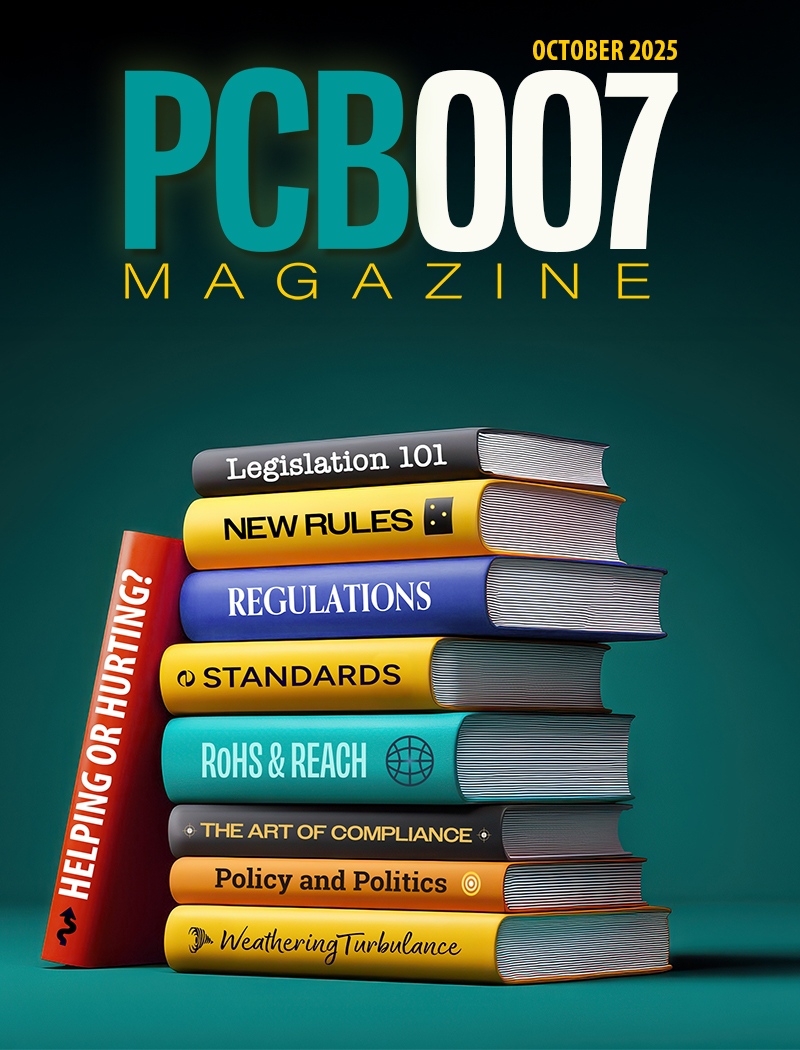

The Legislative Outlook: Helping or Hurting?

This month, we examine the rules and laws shaping the current global business landscape and how these factors may open some doors but may also complicate business operations, making profitability more challenging.

Advancing the Advanced Materials Discussion

Moore’s Law is no more, and the advanced material solutions to grapple with this reality are surprising, stunning, and perhaps a bit daunting. Buckle up for a dive into advanced materials and a glimpse into the next chapters of electronics manufacturing.

Inventing the Future With SEL

Two years after launching its state-of-the-art PCB facility, SEL shares lessons in vision, execution, and innovation, plus insights from industry icons and technology leaders shaping the future of PCB fabrication.

- Articles

- Columns

- Links

- Media kit

||| MENU - pcb007 Magazine

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Testing Flexible Circuits, Part I: Requirements and Procedures

In this first of a three part series regarding tests for flexible circuits, I will examine overall requirements and procedures; the second installment will focus on raw materials, and the third and final part will focus on testing for bare flexible circuit and circuit assemblies.

We get many inquiries that are related to what tests and specifications a flexible circuit should pass. A starting point for specification/testing discussions should start with IPC 6013: Qualification and Performance Specification of Flexible Printed Boards. This comprehensive document can be a starting point for specification/testing discussions, and is often all that is needed, as it provides detailed performance criteria for flexible circuits, including more than 23 different test methods that pertain to the raw materials and final product. In fact, it is universally accepted as the industry standard for flexible circuits. Originally published in 1998, it is periodically updated and revised by an IPC committee that consists of members that represent material suppliers, fabricators, testing facilities, end users and representatives from various associations, as materials, technologies and applications advance.

As most people in the industry are aware, IPC is a global association dedicated to excellence in the printed board manufacturing, electronics assembly and test industry. It is the leading source for standards, test methods, training, market research and policy for its member industries, with a current membership of more than 3500 members worldwide. Originally founded in 1957 as “Institute for Printed Circuits,” the name was subsequently changed to the “Association Connecting Electronics Industries” to reflect its broadening of scope from bare circuit boards to full electronic assemblies.

The IPC 6013 specification recognizes three classifications of flexible circuit boards based on end use applications and defines five types of circuits based on construction.

Performance is specified for the following types of circuit boards, which is taken directly from IPC 6013:

1.3.2 Printed Board Type Performance requirements are established for the different types of flexible printed boards, classified as follows:

Type 1 Single-sided flexible printed boards containing one conductive layer, with or without stiffeners.

Type 2 Double-sided flexible printed boards containing two conductive layers with plated-through holes (PTHs), with or without stiffeners.

Type 3 Multilayer flexible printed boards containing three or more conductive layers with PTHs, with or without stiffeners.

Type 4 Multilayer rigid and flexible material combinations containing three or more conductive layers with PTHs.

Type 5 Flexible or rigid-flex printed boards containing two or more conductive layers without PTHs

A flexible circuit that meets the requirements of IPC 6013 is considered a reliable product for most industries and applications; but what happens when a company has requirements that are not specified in this document? Actually this is fairly common as there many unique applications that, while not covered in this document, are ideal for flexible circuits.

First, many manufacturers have access to a comprehensive database of test results for a variety of applications; often these can be used as a reference point in determining the suitability for an application.

If there is no test data in a circuit manufacturer’s or material supplier’s archives, then it is fairly common that a specific test is developed. One common example is that a circuit needs to survive a submersion test in an unusual chemical. Simply dipping a circuit or circuit material in the chemical may be a very rough starting point, but it should never be considered a conclusive test. In order to truly determine if a given requirement can be met, it must be proven with statistical certainty. This often requires multiple tests and will require input and collaboration from material suppliers. The test itself needs to be statistically valid, so a qualified test engineer would need to design and perform the testing. Even if the test shows statistical confidence, subsequent sampling tests may need to be performed by the material fabricator, the flex manufacturer and/or the end user.

Sometimes, a material supplier is willing to certify that material can pass a certain test, in lieu of any ongoing testing. The end application is generally a significant factor in determining the level of pre-production testing. With applications ranging from toys and games to implantable and life sustaining functions, the level of testing required can vary greatly. Test regimens may take several months, and the supplier will “lock in” a process sequence and manufacturing procedure to best assure minimal variation among parts produced at different times.

Another question we get is related to safety margin in specifications. It is indeed true that when a material supplier certifies that a material will withstand a certain temperature for a certain period of time it was probably tested to a higher temperature. So we might get a question like, “I see that the material is certified to temperature X, but can it withstand X+Y%?” In cases like this some guidance can be provided by material suppliers, but it may be difficult to get a supplier to certify to a “one of a kind” requirement. Agreeing to a higher test parameter is something that the suppliers and end user would have to negotiate. There may be a need to develop added, ongoing testing to assure each lot can pass the specification.

The next column will be focused on testing and specifications at the raw material level. The third column in this series will focus on testing and specification for the finished flex circuit component.

Dave Becker is vice president of sales and marketing at All Flex Flexible Circuits LLC.

More Columns from All About Flex

All About Flex: Terms and ConditionsAll About Flex: ISO 9001 Basics

All About Flex: FAQs on UL Listings for Flexible Circuits

All About Flex: Avoiding Trace Fracturing in a Flexible Circuit

Polyimide vs. Silicone for Flexible Heaters

All About Flex: Copper Thickness Requirements for Flex Circuits

All About Flex: Copper Grain Direction

All About Flex: Options for Purchasing Flexible Heaters