-

-

News

News Highlights

- Books

Featured Books

- pcb007 Magazine

Latest Issues

Current Issue

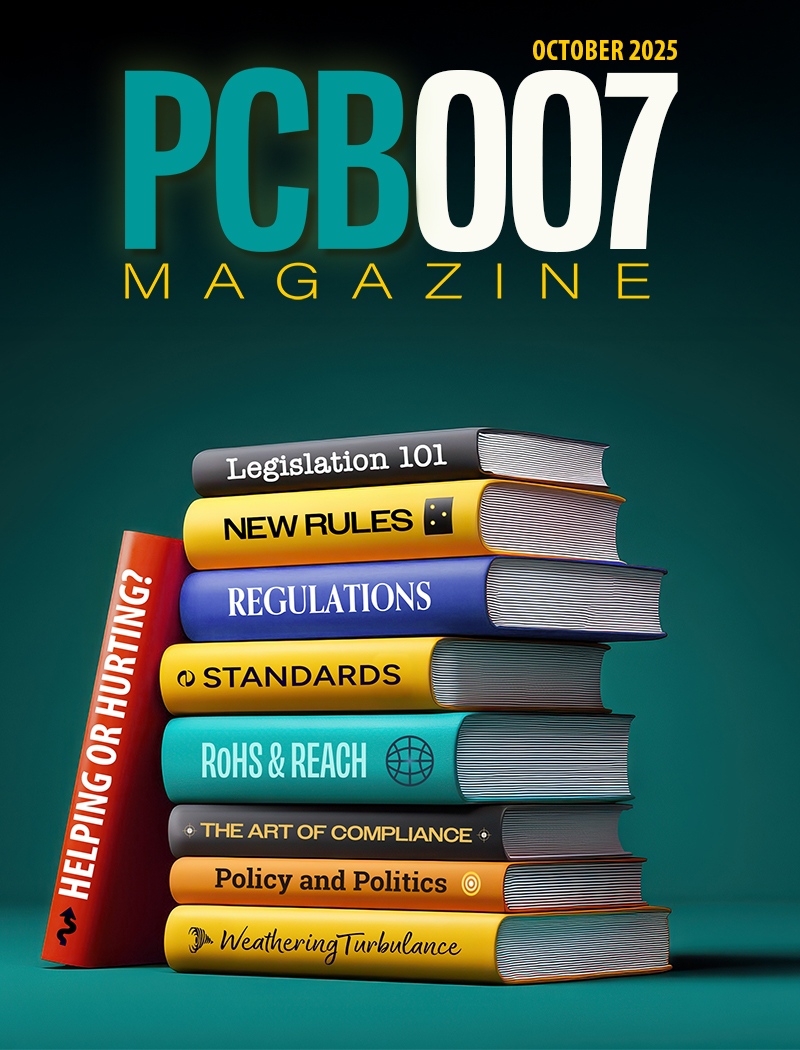

The Legislative Outlook: Helping or Hurting?

This month, we examine the rules and laws shaping the current global business landscape and how these factors may open some doors but may also complicate business operations, making profitability more challenging.

Advancing the Advanced Materials Discussion

Moore’s Law is no more, and the advanced material solutions to grapple with this reality are surprising, stunning, and perhaps a bit daunting. Buckle up for a dive into advanced materials and a glimpse into the next chapters of electronics manufacturing.

Inventing the Future With SEL

Two years after launching its state-of-the-art PCB facility, SEL shares lessons in vision, execution, and innovation, plus insights from industry icons and technology leaders shaping the future of PCB fabrication.

- Articles

- Columns

- Links

- Media kit

||| MENU - pcb007 Magazine

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Contact Columnist Form

Analyzing the Cost of Material in Today’s Global Economy, Part 3

Last month, we continued our discussion on the disparities that exist in the cost of the material associated with electronic product assembly.

This is an important yet often overlooked factor in the ability of an EMS provider or contract manufacturer or original product developer (OPD) to compete in assembling electronic products.

It was recognized that any increase in material cost based solely on an assembly operation’s geographic location could, in itself, cause a condition that would not allow a turnkey electronic product assembler to successfully compete on the global landscape—notwithstanding the difference that exists in direct labor rates.

Previous research has uncovered the fact that material price variation of this kind is present. The magnitude of the price differences cannot be explained by shipping costs or differences in the overhead costs of a particular component manufacturer or distributor's location.1

Considering that material is typically 70–90% of the total recurring production cost of a product, it is clear that even small disparities in material cost as a function of geographic location can bury the effect of labor rate differences. Regardless, it is differences in labor rates that always get the attention of the media and the public.

Why it Matters

In the first column of this series, we established the true variables that affect the ability of a product assembler in a high labor rate location to compete in the global marketplace.2 These are:

1. High assembly-yield loss causing labor costs in high labor rate operations to balloon due to expensive rework. (Not an issue in low labor rate regions where rework labor costs can diminish the effect of poor process development and control.)

2. High indirect and general and administrative labor costs that must be absorbed and greatly inflate the labor sell rate.

3. Material cost differences—a potentially big issue and the subject of this series of columns. This is especially true for tier 3, 4 and 5 operations that don’t have facilities in low labor rate locations. Tier 1 and 2 companies usually have multiple assembly operations with at least one in a low labor rate area. Thus, they can use a central procurement center to leverage volume production for all their facilities and secure favorable low labor rate material pricing across all of their facilities.

4. Government policy such as corporate tax, tariffs and regulation that affects the cost of doing business.

Notice that the differences in direct or raw labor rate as a function of geographic location do not even make the list. Why?

Even though the difference can be substantial, the direct labor rate is a relatively small factor in product cost when examined in the context of reducing labor cost by reducing labor content through automation. This content reduction is realized regardless of where the assembly is being done, but has a far greater impact on cost in high labor rate regions. When the other costs that are associated with variable numbers 1–4 are accumulated and piled on, the difference in direct labor rate has a minor impact on competition.

Of course, companies in high labor-rate regions who have trouble competing will use the pretext of having to go up against uncontrollable, low direct labor rate operations to avoid addressing the controllable root cause of the problem—numbers 1 and 2.

Even though both are controllable through a well-educated staff and workforce, low labor rate competition provides a convenient excuse for failure.

There is similarity here to requiring in-circuit test (ICT) on 100% of the assemblies built even through a 100% functional test will follow. The pretext is ICT is used as a process control tool. Actually, its purpose is to separate the good circuit boards we build from the bad circuit boards we build—those with assembly defects. The good boards go in one pile and the bad ones go into another pile—often the bone pile. As discussed in a previous column, increasing assembly yields can significantly reduce the labor cost associated with rework, as well as the frequency of performing ICT. In fact, if a functional test is being done, ICT can be eliminated altogether. Why? It doesn’t pay back to do ICT on every board if it only identifies 1 in 200 boards tested as having an assembly defect. ICT can then return to its proactive function of helping to validate and control the assembly process.

However, there are valid uncontrollable reasons for competitive cost issues. These are numbers 3 and 4 (unjustified differences in material cost and government policy).

My kingdom for equitable material prices!

Richard the III has abandoned screaming for a horse and has taken up looking for material pricing that is not a function of geographic location. Typically, our assembly house doesn’t because they don’t know any better. Material is material, right?

The assembler generally calls the price paid for this material as raw “M.” It is generally the price paid by the product assembler to the material distributor(s) to purchase the unique material for a particular product assembly. It usually does not include common expendable commodities such as solder and cleaning solutions.

Distributors are the source of this material unless the assembler is ranked as a tier 1 or tier 2 with volume requirements that permit direct purchases from the material manufacturers.

Marking-up the Material

When generating a quote for a turnkey electronic product assembly, the raw “M” is typically marked-up by the assembler to:

1. Absorb the cost of money for the inventory they carry. This is an estimate of what the funds tied up in inventory could have earned if invested, or the interest that needs to be paid on the money borrowed to purchase the material.

2. Pay for the handling the material (inspecting, prepping, kitting).

3. Account for an estimation of material attrition and scrap. Both of these cause the assembler to have to purchase more material than they should have in order to build the required number of assemblies for the customer. Scrap and attrition are the result of material fallout during production. The material losses can be caused by poor product design and component solderability and packaging issues. Also, poor performance of the automated equipment used in the product’s assembly, assembly processes that are incapable and/or uncontrollable, along with other non-conformances increase these losses.

Different companies account for these costs in different ways. Regardless, they must be accounted for.

The inability of assembly operations to properly manage material losses by accurately estimating these losses during the quoting process, and minimizing the losses during the production process, has resulted in many assembly companies effectively wrapping a $5 bill around each assembly they ship—then it’s, “the more we ship to our customer, the more money we lose!”

However, in a business that has razor thin, “supermarket” level margins to begin with, the above issues concerning material performance will not last long (i.e., last person to leave please turn out the lights because the party’s over).

But, this is not what I wanted to discuss in this column. Our immediate interest concerns the cost of the raw “M” to the assembler as a function of the geographic location of the assembly operation.

What contributes to the material cost of an electronic product?

Last month, we listed the cost elements affecting the price the assembler pays the material distributor.3 These are:

1. The cost that the component manufacturers charge the distributors for the material they manufacture.

2. The distributor’s overhead cost that must be loaded and absorbed in the component price.

3. The quantity of material the assembler orders from the distributor.

4. The currency that will be used to pay for the material (e.g., U.S. dollar (USD), yuan, etc.).

5. Any applicable import and export tariffs.

6. And, yes, the location where the material is shipped (although not publicized).

These costs are uncontrollable by the assembler and add up to the ultimate price that the product assembler pays for material. Of course, we are speaking of turnkey product assembly, or at least the turnkey portion of the assembly, as opposed to assembly with consigned material that is provided by the customer.

We went on to focus on uncontrollable material cost variable number 4: how monetary exchange rates affect the price paid for material.

We arrived at the surprising conclusion that a weak yuan, or what politically is the subject of derision in many circles because of alleged unjustified manipulation to keep the currency undervalued, actually should be an advantage to assembly companies paying in USD for electronic product material.

While a disadvantage for assembly labor in high U.S. dollar labor rate markets, a weak yuan should be an advantage in a strong currency environment because the material should be less expensive to purchase (i.e., a strong dollar buys more yuans, or buys material at a reduced price).

What is it then?

If it’s not exchange rates (cost variable number 4), it’s got to be the distributors running two sets of books—one for customers in the high labor-rate world and one for those in low labor-rate regions.

Do the distributors have dual pricing structures because the component manufacturers charge them more if they are distributing to assemblers in high labor-rate areas?

Is it because of distributor overhead costs are much more in high labor-rate areas—material cost variable number 2? This was looked at in detail and the material price disparity could not be justified by this factor.4

That leaves material cost elements 5 and 6. Item 5, import and export tariffs, is generally applied to assembled products, not raw or manufactured (inseparable) material such as electronic components. However, this is a complex subject and is dependent on the specific material of interest. It will be addressed in more detail next month in the final column on the subject of analyzing the cost of material.

Then, what remains to explain the significant difference in material pricing for product assembly depending on where that assembly is done? Without the curiosity to first obtain the data and then challenge the data, we stop here and say, “It’s just the way it is.”

Data Explosion and Assimilation

I remember in the early 1970s, at the dawn of the digital revolution, some suggested that twice as much data and information existed in 1970 as in 1960. And, therein lies the rub. Data and information are pretty much useless until codified into knowledge. Applying critical thinking to the knowledge can allow it to be transformed into wisdom. This is what is commonly called the DIKW (data, information, knowledge, wisdom) hierarchy or pyramid. In my view, it is the responsibility of the educational system to provide the students with knowledge and teach them how to find the path to wisdom.

How does a public education system grapple with these geometric data and information explosions? The massive amount of information added to the public domain certainly hasn’t stopped since 1970 and shows no sign of doing so in 2017 and beyond.

An educational system can capture the data and information in a digital format and store it on hard drives. It can teach the student how to access the information and require the student to glimpse into this cloud, memorizing certain information strings. However, unless the educational system can successfully help the student construct ladders to convert the information into knowledge, and then the knowledge into wisdom, their job is woefully incomplete.

This is the challenge facing our educational system. It will not be met by continuing a system that is failing or trying to improve by nibbling around the edges. The system must find a way to engender all students’ curiosity and develop in them a love for learning that will last throughout the student’s life.

It is tempting to say everything will change so why bother. Either just start by teaching the student the latest ‘gee whiz’ data, or continue to teach what is obsolete and is of little value to them in the real world. Since relativism is the soup du jour, you are what you think—there is no absolute.

An alternative is to suggest certain basic tenets and values will transcend the onslaught of new data and information—the wisdom will always remain true. There is not one ladder that leads to that wisdom, but many. On the journey, we jump from one ladder to another like Mario on a Pac-man™ screen.

In his 1995 book, Nicholas Negroponte discusses an economy based on atoms versus an economy based on bits.5 We are taxed and the market assigns value to the magazine we buy at the newsstand, but not on the content on the hard drive in our laptop. What would you say the value of your laptop is to you? Is it the $3000 you paid for it, or is it a lot more based on the 1s and 0s you have added to the hard drive or the cloud? What value do you declare for your computer when going through customs?

Will the issue of the price we pay for electronic components become moot and evaporate when we are able to create components or assembled products by simply printing them in our office? Will the human machine interface (HMI) for the pick-and-place machine become considerably less expensive when we will be able to directly program and control the machine with our brain? Will we even need a pick-and-place machine to assemble an electronic product?

Hey, what do YOU say? I’d like to hear your thoughts, reactions and opinions.

We’ll wrap up our discussion on material pricing next month with input from people close to the uncontrollable material cost variables we have discussed in this column.

References

1. T. Borkes, “Electronic Product Assembly in the Global Marketplace: The Material Piece of the Competitive Puzzle,” SMTA International Conference Proceedings, Orlando, Fl., October 2010.

2. T. Borkes, “Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking and Analyzing the Cost of Material in Today’s Global Economy, Part 1,” SMT Magazine, June 2017.

3. T. Borkes, “Analyzing the Cost of Material in Today’s Global Economy, Part 2,” SMT Magazine, July 2017.

4. T. Borkes, “Electronic Product Assembly in the Global Marketplace: The Material Piece of the Competitive Puzzle,” SMTA International Conference Proceedings, Orlando, Fl., October 2010.

5. N. Negroponte, Being Digital, Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

More Columns from Jumping Off the Bandwagon

The Proper Position to Take on Voids in Solder JointsAnalyzing Material Cost in Today’s Global Economy—Hit the “Pause” Button

Analyzing the Cost of Material in Today’s Global Economy, Part 2

Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking and Analyzing Material Cost in the Global Economy, Part 1

A New Organizational Model Using Logic, Cost-Effectiveness and Customer Service, Part 3

A New Organizational Model Using Logic, Cost-Effectiveness and Customer Service, Part 1

Leadership in Your Company: Something to Worry About?

A New Organizational Model Using Logic, Cost-Effectiveness and Customer Service, Part 2